Summary

15 March 1948 – 19 August 2003

Sergio Vieira de Mello was born on March 15th 1948 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He lived abroad from a young age having had a father who was a diplomat and a historian. Once back in Brazil, Sergio finished his secondary school education in the Lycée Franco-Brésilien in Rio, graduating with a baccalaureate in Classical Literature. In 1966, in an effort to be close to his father, then Consul General in Stuttgart, Germany, Sergio moved to Switzerland to study philosophy at the University of Fribourg. He subsequently moved to Paris to pursue his education, graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in 1969 and a Master’s degree in 1970, both in Philosophy from the Sorbonne University.

Sergio joined the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as a French Editor when Sadruddin Aga Khan was High Commissioner. While holding this position, he finished his third cycle Ph.D in 1974 (with honours) at the Sorbonne. He later obtained his “State Doctorate” in 1985.

Following the proclamation of independence of “East Pakistan” in December 1971, UNHCR undertook an unprecedented repatriation operation. In the context of this gigantic undertaking, Sergio Vieira de Mello then aged 23, was sent to Dhaka to work on ensuring the successful repatriation and reintegration of the Bengali refugees who fled to India to escape the civil war. In the five months of that assignment, Sergio was a witness to the birth of a new state—Bangladesh.

In the summer of 1972, Sergio was again assigned to the field to help in another UNHCR operation in South Sudan. Again at the young age of 24, he actively participated in the repatriation and reintegration of hundreds of thousands of South Sudanese refugees who had fled the country during the civil war. Upon returning to Europe, he got married in France in the summer of 1973 to Annie.

In the following year, Sergio was assigned to Cyprus, first to South Nicosia, then to North Nicosia as the Head of the UNHCR programme for the island.

On June 25th 1975, Mozambique, a former Portuguese colony, became independent, Sergio, accompanied by his wife Annie, left for Mozambique to take charge once again of the repatriation operation and the reintegration of Mozambicans who had fled the country during the war. When the UNHCR Representative in Maputo completed his assignment, Sergio, at age 28, took command of the UNHCR office in the country becoming one of the youngest UNHCR Representatives in the field.

In the beginning of 1978, Sergio was named Regional Representative for UNHCR to Peru. Sergio was just turning 30. He left with his family for Lima where their first son, Laurent was born in mid-1978. Sergio and his family stayed in Peru for two years while essentially negotiating the repatriation, particularly to Europe, of thousands of Latin American refugees who had initially gone to Chile under the Allende regime, and later fled to Peru following the coup d’Etat of Augusto Pinochet.

In January 1980, Sergio returned to Geneva to take up a post in the Personnel Division of UNHCR where he was responsible for shaping the careers of many international civil servants. His second son Adrien was born in the same year.

In November 1981, after having spent 20 months in Geneva, Sergio was seconded by UNHCR as Political Affairs Advisor to the United Nations Interim Forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL). This first experience, as part of a peace-keeping operation, led him to appreciate the complexities of such operations and drew him close to the military. In July 1983, Sergio Vieira de Mello returned to Geneva to resume his functions in the Personnel Division at UNHCR Headquarters.

He spent the next ten years at the Headquarters occupying different positions within the organization. During that decade, he would be named to serve in Buenos Aires, only to be quickly recalled when the new High Commissioner Jean-Pierre Hocké took office in 1986, to serve as his Chef de Cabinet. Sergio benefited from the period of stability in Geneva to finish his doctorate thesis “Civitas Maxima” for which he received a “very honourable “mention from The Sorbonne in Paris in December 1985.

During the years spent at UNHCR Headquarters, Sergio occupied the position of Chef de Cabinet to the High Commissioner, Secretary of the Executive Committee and in May 1988 he became Director of the Asia Bureau and subsequently occupied the post of Director for External Affairs. In the context of his work in the Asia Bureau, he was the main initiator of the Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) which put an end to the exodus of the Vietnamese “boat people”, who were still leaving Vietnam ten years after the end of hostilities. For that purpose, Sergio managed to bring all stakeholders to the negotiating table, notably the administrations in Washington and Hanoi, which in 1980 was an accomplishment, as the scars of the Vietnamese war were far from healed in both countries.

At the end of 1991, the new High Commissioner for Refugees, Mrs Sadako Ogata, named Sergio as her Special Envoy in Cambodia. He simultaneously assumed the responsibility of the Head of the Division of Repatriation of the United Nations Transitional Authority for Cambodia (UNTAC). This operation was considered a successful one for the United Nations. In June 1993, around 370,000 Cambodians returned home to their villages.

On returning to Geneva in the summer of 1993, Sergio had to leave again in the autumn of the same year to Bosnia to take part in a peace-keeping operation. In October 1993, he became the Political Director for UNPROFOR in Sarajevo, then in April 1994, he was stationed in Zagreb as Head of Civil Affairs.

Sergio returned to UNHCR Headquarters in Geneva in October and became Director of Planning and Operations. One of the main accomplishments in this post was the organization of the Conference on Refugees and Population Movements in the Community of Independent States (CIS). The Conference took place in Geneva in May 1996 and adopted a Plan of Action, the goal of which was to control and channel the influx of migration as a result of the break up of the ex-Soviet Republics. In January 1996, Sergio was promoted to the position of Assistant Secretary-General and became the first Assistant-High Commissioner for Refugees.

In October 1996 Sergio Vieira de Mello was again detached from UNHCR and named as Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the Great Lakes Region. He performed the functions of Humanitarian Coordinator for the three months of his assignment (October-December 1996). He returned to Geneva at the beginning of 1997 to resume his functions as Assistant High Commissioner in UNHCR.

In January 1998, Mr. Kofi Annan, who took office as Secretary-General of the United Nations a year earlier, appointed Sergio Vieira de Mello as Under Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Head of of the Office of Coordination of Humanirarian Affairs (OCHA) in New York. Sergio undertook, at the request of the Secretary-General, an evaluation mission to Kosovo (UNMIK). Upon his return to New York, he delivered his report to the Security Council and was shortly afterwards named by the Secretary-General as his Special Representative in charge of the United Nations Interim Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). Upon his return to New York in July 1999, he resumed his function as Head of OCHA.

In November 1999, after the Security Council adopted a resolution on September 15th creating the International Forces of Intervention (INTERFRET) and a subsequent resolution on 25th October creating the United Nations transitional Authority for East Timor (UNTAET), Sergio Vieira de Mello took over as Administrator of UNTAET in Dili. From November 1999 until April 2002, Sergio was the de-facto Governor of East Timor. Timor Leste was later created on May 20th 2002 with Xanana Gusmao becoming its first President.

In September 2002, Sergio was named by the Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, as High Commissioner for Human Rights, based in Geneva. He remained in his new post until the end of May 2003, when the Secretary-General, asked him to serve as his Special Representative in Baghdad for four months. Sergio arrived in Iraq on June 2nd 2003. On July 22nd , he delivered his report on the situation in Iraq to the Security Council, noting the particularly difficult conditions under which the United Nations had to work in the country.

Sergio Vieira de Mello was killed in Baghdad, with 21 of his colleagues, in the bloodiest attack that ever targeted the United Nations in its long history, on the afternoon of August 19th.

The world was stunned. The deep sense of loss that accompanied Sergio’s tragic abrupt departure grew into a swell of unprecedented grief and despair. It is difficult to select what sentiment best represented the mood of gloom and emptiness worldwide that followed Sergio’s untimely departure but one obituary stand out because of its sheer simplicity… it came from the heart.

Former UNHCR Assistant High Commissioner and close friend Kamel Morjane: “At the UNHCR, where he spent 25 years of his life, he was the brilliant son that his elders would have wished to have. For his peers, like me, he was the colleague or the friend, often both, that one tried to emulate and hold up as an example, but one was never able to equal”.

Throughout his long illustrious career, Sergio was supported, encouraged and protected quietly from behind the scene by his wife Annie as both watched with pride their sons Laurent and Adrien grow and bloom into successful young men. As a family, they will continue to miss their beloved Sergio very dearly.

After lying in state in his native Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Geneva, a city that had become a second home to him and whose citizens lined the streets to pay him their last respects, Sergio Vieira de Mello was laid to rest in the Cimetière des Rois (the Cemetery of Kings) in Geneva on 28th August 2003.

May his soul rest in eternal peace

Timeline

1969 – 1971

French Editor, UNHCR, Geneva, 1969-1971

• UNHCR shifts attention from Europe to Africa and Asia.

• High Commissioner Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan adapts organization to universality of its mandate to also cover political intervention on behalf of refugees.

• Bangladesh, Uganda and Sudan become countries of focus for repatriation and resettlement.

• Young talent in a transforming organization.

UNHCR in early Seventies

1. Until 1964, some refugees were described as benefiting from the High Commissioner’s good offices, and others as falling within his mandate. From 1966 onwards, however, the General Assembly ceased to make this distinction, requesting the High Commissioner to “continue to provide international protection to refugees who are his concern, within the limits of his competence, and to promote permanent solutions to their problems.” Later, in December 1972, to allow UNHCR to assist in the repatriation of Southern Sudanese refugees from neighbouring countries and also to resettle those who had been displaced within their own country, the Assembly referred at one and the same time to refugees and displaced persons as coming within the competence of the High Commissioner. In 1975, an important step was taken when Resolution 3454 of December 9, reaffirmed in its preamble “the essentially humanitarian character of the activities of the High Commissioner for the benefit of refugees and displaced persons.” This era of the organization coincided with the leadership of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan at the helm of UNHCR as its High Commissioner. He is widely credited as the man who put UNHCR on the map.

2. The organization’s expenditure in Africa and Asia for the first time exceeded that in Europe, marking a clear shift from Europe to the developing world. The High Commissioner strengthened relations with african governments and helped to improve inter-agency cooperation within the United Nations to address the problems of mass displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. The high points of his tenure were UNHCR’s major role in assisting the Bangladesh refugee crisis in 1971, the Asians expelled from Uganda in 1972 and in the massive repatriation and resettlement of the Southern Sudanese refugees in 1972 following the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement.

Achievements

3. Sergio Vieira de Mello graduated from the Sorbonne, France in 1969 majoring in Philosophy. His suspension from the Sorbonne in 1968 for student activism and the forced retirement of his father, then Brazilian Consul-General in Stuttgart, Germany in1969 by the Brazilian military government of the time, did not prevent him from graduating from the Sorbonne. This spirit of indomitable determination in the face of adversity would in later life serve him well time and again whenever he was caught in situations that ordinary beings would despair of.

4. At the young age of 21, Sergio finding himself in Geneva, decided to try his luck at jobs at the United Nations. He was received by the then Chief of Personnel at the Palais des Nations, Jean Halperin. Impressed by the young man’s articulate demeanor but leary of the relevance of his philosophy qualification, he offered to give him a temporary job as a messenger during the ECOSOC session. A few days later the Head of the Secretariat at the UNHCR, asked Jean Halperin to recommend a good young bilingual writer/editor to him. He immediately remembered Sergio. Advising Sergio that the job was not exciting nor exalting, Mr. Halperin recommended him to UNHCR. Thus begun the entry of Sergio into UNHCR on a career path that would span thirty years. Jean Halperin, would in later years recollect his particular role in launching Sergio in the UN system in these words “I had the extraordinary good fortune of bringing him into the UN… putting him into orbit! Given, of course, that all the rest was entirely due to his own merit”.

5. In conformity with his ideals for fairness, justice and respect for basic human rights so well imbued into him by his solid grounding and passion in philosophy, Sergio found it easy to adjust to and internalize the lofty mission of the UN and particularly its humanitarian and humanistic objectives and goals. He was convinced, very early in his career, that the UN could not make headway on effective humanitarian response and sustainable peace building without embarking on and promoting dialogue for the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

6. Sergio’s first assignment in UNHCR at the entry P1 level as French Editor, coincided with the transformation of the organization from concerns with the legal protection of refugees and their integration in their countries of first asylum or their resettlement in third countries, to an international operational agency with a wider stronger mandate. High Commissioner Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan resolved to adapt the organization to new realities and demonstrate the universality of his mandate. By intervening, not only in the field, but also, at the political level to find solutions, he laid the foundation for modern humanitarian action. He was supported by a dedicated team of experienced UNHCR staff and a new generation of talented young men and women including Sergio who later grew into the organization’s shakers and movers. Many would later express admiration for Sergio’s outstanding leadership quality and his warm heart for colleagues and friends.

7. Sergio was attached to UNHCR’s Secretariat, responsible for all official correspondence as well as for preparing reports for Governments, the UN General Assembly and the Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s programme. This was an excellent training ground for Sergio in refining his diplomatic skills and ability to relate to and work with governments which would in his later career prove invaluable. Within two years of joining UNHCR, Sergio was assigned to the field – East Pakistan (Bangladesh) – starting a long illustrious field career with which he would be prominently associated and immensely appreciated within as well as outside the Organization.

1971 – 1972

Project Officer, UNHCR, Dhâkâ, East Pakistan 1971-1972

• Bloody Rebellion for independence from Pakistan.

• 10 million fled as refugees to India.

• All refugees returned home and were resettled.

Prevailing Situation in East Pakistan in 1971

1. In 1971 East Pakistan under the leadership of Mujibur Rahman rebelled against the Pakistani authorities and demanded independence. The violence that was unleashed drove 10 million refugees across the border into India. All efforts at reconciliation failed. India concerned over the violent eruptions on its border and the massive influx of refugees on its soil, declared war against Pakistan on 6th December 1971.Ten days later Mujibur Rahman declared the secessionist province independent. A new nation : Bangladesh came into being.

2. The tension between India and Pakistan over the Bangladesh crisis placed UNHCR High Commissioner for Refugees, Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan before a dilemma. On the one hand he was anxious to put an end to the suffering of the ten million Bengali refugees in India by repatriating them voluntarily. On the other, he knew well that this could not be achieved without a successful dialogue and reconciliation between India and Pakistan. He embarked on a shuttle diplomacy between the two nations. He designated an outstanding staff, John Kelly, known for his negotiating skills, accompanied by Sergio Vieira de Mello, who was likewise gifted for diplomacy and dialogue, to undertake a mission to Dhâkâ to establish a UNHCR presence. The team was supported at the Geneva end by the then Programme Officer Catherine Bertrand. The mission to East Pakistan was a success. By the time the massive exodus of returnees begun in India, UNHCR was strategically established to receive them back or resettle them.

Achievements

3. Sergio’s short assignment in Bangladesh coming early in his formative years, was rewarding and the experience would prove invaluable to him in his later career. It is best summed up by his own testimony in latter years to a close friend, “It was an extraordinary experience. I was 23, the age of one of my sons today. I witnessed the painful birth of a nation”. If anything, the assignment convinced Sergio more than ever before of the crucial importance of dialogue in creating the conducive environment for reconciliation and sustainable peace and development.

1972 – 1973

Programme Officer, UNHCR, Juba, Sudan 1972-1973

• Long brutal Civil War

• Hundreds of thousands killed

• 250,000 refugees in neighbouring countries

• 600,000 internally displaced

• 200,000 refugees repatriated and reintegrated or resettled

Prevailing Situation in the Sudan in early Seventies

1. Independence came to the Sudan in 1956 over the strong objection of the Southern Sudanese who wanted an interim period of preparation in education, public service and democracy under the British before deciding on their future. The mutiny by Sudan Defence Force (SDF) in August1955 in Torit, Equatoria Province, was the climax of the resentment of frustrated Southerners to what they perceived to be a total northern domination of all facets of life. The period 1956-1972 was marked by severe repression of the Southern Christians and animists by successive northern governments who viewed them as harbouring secessionist ambitions. Indiscriminate killings, maiming and massive displacements became the order of the day. Hundreds of thousands were killed and 250,000 fled and became refugees in the neighbouring countries of Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Central African Republic (CAR) and Zaire. Over 600,000 helpless victims were internally displaced and forced to eke out a living in squalid inhuman conditions.

2. The armed Southern struggle against the North grew into a formidable movement known popularly as Anya Anya (Snake Venom) led by a young army Officer Lt Joseph Lagu, later to become a general, who had deserted the Northern army. The long guerrilla warfare that lasted for 17 years brought the case of the Southern Sudan forcefully to the attention of the world. Nevertheless, the devastating effects of the war and the severe northern suppression created havoc and immeasurable suffering for the population. The situation was exacerbated by the world looking the other way and the unrelenting Civil War became better known as “The Forgotten War”.

3. It was only the successful conclusion of the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement between the North and South in February 1972 in the Ethiopian capital, under the aegis of Emperor Haile Selassie, that brought a cessation of hostilities and peace to the Sudan. The South was granted Regional Autonomy and a highly respected Southern Lawyer Abel Alier became the first President of Southern Sudan. General Joseph Lagu assumed the command of the integrated division of the Sudan Army based in the South with its Headquarters in Juba. The country turned now to the challenging task of receiving back millions of refugees and embarking on the reconstruction and development of the Southern Sudan. The international community led by UNHCR came readily to the assistance and support of the fledgling region.

Achievements

4. At the young age of 24, hardly three years since he first joined UNHCR, Sergio Vieira de Mello was reassigned from Dhâkâ, Bangladesh and posted to Juba, Southern Sudan. His assignment coincided with the coming into force of the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement. The then High Commissioner for Refugees Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, had played a significant role from behind the scene in the conclusion of the Peace Agreement and had therefore a vested interest in the successful repatriation and resettlement of the refugees. It was therefore no accident that the High Commissioner ensured that the Organization’s best young talents represented by Sergio, formed the backbone of UNHCR’s dedicated core staff to tackle the challenging assignment.

5. His previous assignment in Bangladesh where UNHCR helped resettle a massive number of returnees, prepared Sergio well for his new responsibilities. Under the overall management of Thomas Jamieson, and supported by then Programme Officer Catherine Bertrand in Geneva, he operated from the UNHCR Sub-Office in Juba as his base. From this vantage point, Sergio oversaw the distribution of food, clothing, medical supplies and building materials to the returnees working closely with the other collaborating partners. Receiving, transporting and repatriating 200,000 refugees to their villages and communities of origin was a major part of Sergio’s responsibilities. Overall 1,190,320 people, including those internally displaced, emerged from the bush and returned to their original homes. He fulfilled these responsibilities brilliantly, gaining appreciation and praise from his peers and superiors alike. Above all, his great gift for dialogue and reconciliation found ample expression in his daily interactions with the restive returnees who came from diverse background and tribal affiliations. Although their expectations were sometimes unrealistic they could easily identify with and looked up to Sergio as the one who built understanding and consensus through dialogue and solved their problems.

6. Transportation and logistics problems were major hurdles to UNHCR carrying out its enormous tasks of repatriating the returnees. River transport from the North to the South was slow. Within the South itself, roads were unusable either because of rains or long disuse. The most challenging feat was the transportation of people especially returnees and goods arriving from Uganda and Kenya across the Nile into Juba. This bottleneck was broken when the Netherlands contributed a prefabricated bridge to UNHCR’s programme for Southern Sudan. It required a work of colossal engineering feat to transport the components of the bridge to Juba and re-assemble it across the Nile. The bridge not only replaced the antiquated ferry but to this day remains the most vital link of Southern Sudan to East Africa. Sergio and his colleagues must be complimented for their foresight in negotiating the donation and construction of this key bridge across the Nile, at Juba.

7. Sergio left Juba and Sudan in June 1973 after UNHCR had assisted the Regional Government of Southern Sudan to repatriate and reintegrate 200,000 returnees and 600,000 IDPs, paving the way for recovery, reconstruction and development. Of lasting legacy to the people of Southern Sudan was UNHCR’s decision to go beyond its relief mandate for refugees to rebuild hospitals, schools, roads and bridges and revive agriculture. Sergio was very much behind these advanced thinking and creative policy. To his credit, Sergio not only discharged his UNHCR responsibilities with distinction but also left behind the lasting memory of a dedicated young man driven by the passion for dialogue and reconciliation.

1974 – 1975

Programme Officer, UNHCR, Nicosia, Cyprus 1974-1975

• Tension between Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

• Turkey invaded north Cyprus and Turkish Air Force bombed main Cypriot cities.

• 180,000 Greek Cypriots fled to south of island and 11,000 Turkish Cypriots transferred to northern, Turkish occupied zone.

• A divided island.

• All displaced Greek and Turkish Cypriot populations resettled.

Prevailing Situation in Cyprus in mid-Seventies

1. Since gaining independence from the British in 1960, Cyprus has been beset by tensions between its majority Greek and minority Turkish populations. This came to a head in the summer of 1974 when Turkey invaded and occupied an enclave in the north of the island and its Air Force bombed the main cities. 180,000 Greek Cypriots fled to the south and 11,000 Turkish Cypriots were transferred to the northern third of the island occupied by Turkey. The gravity of the situation was underscored by the fact that at the time of the crisis, the displaced population of 191,000 equaled about one third of the total population of the island! The UN Peace-Keeping troops deployed on the island since 1964, could not calm the tension and all it could do was to deploy along the ceasefire line, ostensibly to prevent direct confrontation and violence. The island has remained divided right across the capital, Nicosia to this day.

2. In 1974, at the request of the then UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim, the High Commissioner for Refugees, Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, launched what came to be known as the “Special Humanitarian Operations” to address the problems of the displaced populations of Cyprus. Sergio Vieira de Mello was a member of the team that UNHCR deployed on the island. The team’s assignment was to provide relief assistance, to build and extend schools and hospitals and to create employment for the affected populations.

Achievements

3. Sergio was assigned to the north to take care of the displaced Turkish Cypriots. Bangladesh and Sudan had prepared him well for his new role. Cyprus became a very important milestone in Sergio’s life. It was to be his first contact with the military, an encounter that would in coming years grow into an enduring relationship of friendship and mutual admiration. Sergio loved the discipline and culture of the military and trusted them. Although the nature of the problems and needs of the IDPs in Cyprus were unique to the island, Sergio and the team met the High Commissioner’s expectation. The Special Humanitarian Operations was a resounding success.

4. His location in the north placed Sergio in a delicate position. To get things done, he had to deal daily and negotiate continuously with both the UN Peacekeeping troops as well as the occupying Turkish forces. He relied on his knack for diplomacy and passion for dialogue and reconciliation to cut through red tape and bureaucracy. In the end, the real beneficiaries of Sergio’s efforts were the displaced populations of Cyprus who were able to find new homes and care and rebuild their lives.

1975 – 1977

Deputy Representative and Representative, UNHCR, Maputo, Mozambique 1975-1977

• A twelve-year bitter war of liberation.

• Hundreds of thousands either fled and took refuge in neighbouring countries or tried to survive in squalid conditions as IDPs.

• 26,000 Zimbabwean refugees in Mozambique and thousands bombed by Rhodesian air force.

• 80,000 returnees repatriated and reintegrated.

• 500,000 IDPs reintegrated.

Prevailing Situation in Mozambique in mid-Seventies

1. In April 1974, a revolution in Portugal brought into power a more progressive regime that adopted radical policy changes, especially on decolonization. It negotiated independence for its African colonies : Mozambique, Angola and Guinea Bissau. For Mozambique, the ten-year war of liberation that caused tens of thousands of people to flee and seek sanctuary in neighbouring countries, ended with independence in 1975. On 25 June 1975, the Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique) leader Samora Machel became the country’s first President. Massive repatriation and reintegration of refugees became the most challenging task for the fledgling government. Fortunately, UNHCR had the foresight to begin establishing a robust presence in the country to support the government in receiving and handling the massive case load of refugees.

2. The new government soon allied itself with the liberation wars in Zimbabwe, then Rhodesia, and South Africa. This provoked indignation and full scale reprisals by the oppressive racist regimes of the countries against Mozambique. Matters came to a climax when in August 1976, the Rhodesian regime launched a devastating air raid that killed thousands of refugees in a camp close to the border, under the care of UNHCR. The High Commissioner for Refugees, Sadruddin Aga Khan, describing the incident as abominable, reacted angrily, “It escapes my understanding as to what those responsible for it thought they were accomplishing through such an atrocity.”

3. As if the confrontation with South Africa and Rhodesia were not enough, President Samora Machel signed a treaty of co-operation and friendship with the Soviet Union that was not accepted by all Mozambicans. This plunged the young country into civil war in 1976.

Achievements

4. Sergio Vieira de Mello was appointed by the High Commissioner for Refugees as Deputy UNHCR Representative and re-assigned from Cyprus to Maputo in July 1975. He arrived to take up his new assignment on very day of Independence when the new government with whom he would work closely, took office. Sergio took over as Acting Representative after one and half years and oversaw Mozambiques’s major repatriation and reintegration operations.

5. The influx of the returnees started in mid 1975.With $7million at it disposal, UNHCR launched an organized programme that repatriated and reintegrated 80,000 returnees and reintegrated 500,0000 IDPs in their original communities. These affected populations were assisted mostly through the provision of tools, implements and seeds to resume agriculture and shelter to rebuild their lives. UNHCR gave them food until harvests were adequate. The Zimbabwean refugees were repatriated much later in 1980 when the country gained independence. Sergio relied on his blossoming diplomatic skills and passion for dialogue and reconciliation to facilitate his delicate work with the fledgling government and the returnees and IDPs who came to trust him. He handed over to Anne Willem Bijleveld and left Mozambique in September 1977 to Lima, Peru, as UNHCR regional representative. He was to return to the African continent years much later.

1978 – 1980

Representative, UNHCR, Lima, Peru 1978-1980

• Right-wing dictatorships take power in various latin american countries.

• Right-wing military coup in Chile forced tens of thousands of leftist Chileans and those suspected of leftwing sympathies to flee into neighbouring countries.

• Trend repeated in Argentina, Bolivia and Peru creating a massive case load of refugees across Latin America.

• Responsibilities of providing protection, relief assistance, repatriation and resettlement major challenges for UNHCR.

• Asylees and refugees resettled mainly in Europe.

Prevailing Situation in Peru in late Seventies

1. On 11th September 1973 General Augusto Pinochet overthrew the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende and seized power in Chile. This ushered in a wave of right-wing dictatorships soon to spread to Argentina, Bolivia and Peru. In Chile the change suddenly placed the lives of tens of thousands of Chileans in danger. All the leftist elites including politicians lawyers, academics, journalists and other professions became suspect and were hunted down. The repressive rule marked by harassment, arrests, torture and assassinations was extended to labour leaders and workers as well as students. Many of these targeted victims were compelled to seek refuge in neighbouring countries, Europe and North America. They needed UNHCR’s protection.

2. By a cruel twist of history, Chile had previously under Allende offered asylum to refugees fleeing other dictatorships in Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay and Paraguay. Chile which had by then acceded under Allende to the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocal guaranteeing international protection to refugees, viewed the gesture as Chile’s commitment to compliance with the international protection instruments. These asylees found themselves suddenly in danger and looked to UNHCR for protection.

3. The UNHCR High Commissioner, Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, telegraphed Pinochet reminding him of his country’s international obligations. A UNHCR team under the overall responsibility of its Regional Office in Buenos Aires, was sent to Santiago to attend to the urgent needs of the asylees. They were swiftly resettled mainly in Europe. Although several Chileans were lucky to find asylum in Europe, thousands were compelled to cross into neighbouring countries as refugees. Conditions for them were not better then what they had left behind. A large number went to Argentina where Peron’s populist regime welcomed them with open arms. Brazil and Peru, although signatories to the international refugee instruments, reluctantly accepted several thousands, partly because they were military governments whose right-wing views were close to Pinochet’s. These dictators demanded and obtained that the refugees remain under the sole protection of UNHCR until such time that countries could be found outside the region willing to accept them. Thus, UNHCR was compelled to open offices in Rio de Janeiro and Lima to protect the refugees and organize their resettlement in third countries.

4. The refugee situation in Latin America was further compounded when on 24th Mach 1976 a military junta led by General Jorge Rafael Videla seized power in Argentina. The infamous “Dirty War” that followed forced thousands of Argentines pursued even beyond their borders, to go into exile. They, like the Chileans before them, felt threatened wherever they went in Latin America. At about that time, whereas asylum countries in Europe had shown great generosity in the early days, the pool of visas for refugees began to dwindle and the laudable spirit of welcome petered out. This problem was most sharply felt in Peru were the Chilean refugees lacking any form of productive activities and losing hope of resuming normal life turned to UNHCR to vent their anger and frustration. They occupied the UNHCR Office and protested their case.

Achievements

5. Sergio Vieira de Mello was re-assigned by the High Commissioner to head the Lima Office which was then occupied by refugees. At the age of thirty, Sergio was propably the youngest representative in UNHCR history. His first task was to enter into dialogue with the refugees and negotiate their withdrawal from the office. It was not an easy task but he summoned his now well developed skills at diplomacy and negotiations to bring the matter to a satisfactory solution for the government, the refugees as well as for UNHCR. The organization was able to resume its normal functions and the Lima Office was upgraded to report directly to the UNHCR Headquarters in Geneva.

6. Looking back to his assignment in Peru, Sergio treasured two things very dearly. Having lived part of the political turmoil in the country, it was a great source of joy and happiness for him to see the end of the military regime and witness 850,000 indigenous Peruvians vote in a democratic election!

Secondly for the first time, he had the experience of dealing with individual refugee cases. According to him, “I knew them by their names, their smiles, their songs and their tears”.

1980 – 1981

Head of Career Development and Training Unit of Personnel Section, UNHCR, Geneva, January 1980-1981

• UNHCR becomes highly operational but the need for qualified professional cadre persisted.

• Tens of thousands of Vietnamese refugees “Boat People,” dominated refugee case load

• UNHCR wins Nobel Peace Prize for second time.

• UNHCR strengthens collaboration with traditional NGO partners.

• Comprehensive Staff Development Programme and Emergency Unit launched.

UNHCR in early Eighties

1. By the early eighties, UNHCR, under High Commissioner Poul Hartling was facing new challenges as refugee problems became highly politicized, especially with the intensification of the Cold War. The sustained mass exodus in Indochina and a large scale international response thrust the organization into a vast humanitarian operation. UNHCR set up other major emergency relief operations in the Horn of Africa and Central America, and for Afghan refugees in Asia. The organization was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for a second time in 1981 in recognition, largely, for its outstanding work in managing the Vietnamese refugee crisis, while undertaking major operations on behalf of Afghan and Cambodian refugees.

2. In 1982, the number of refugees under UNHCR mandate exceeded 10 million. In Southeast Asia tens of thousands of Vietnamese refugees (“Boat People”) languished in camps, expecting resettlement opportunities outside the region. Millions of Afghan refugees who had fled the Soviet occupation of their country swarmed in camps in Pakistan and Iran. The traditional solution of resettling refugees in third countries became untenable and unrealistic for the majority of the world’s refugees. UNHCR came to the conclusion that voluntary repatriation was the only realistic durable solution to end the suffering of the refugees in camps in Asia, Africa and Central America. The period 1979-1981 was characterized by an unprecedented expansion of UNHCR’s activities, mainly in South East Asia. The staff strength grew from a total of 730 in 1979 to over 1600 in 1981! To cope with the new expanded work load, High Commissioner Hartling directed the strengthening of the organization’s capacity in a variety of ways. Much of the responsibilities for translating this decision into action lay with the Career Development and Training Unit which cooperated closely with newly created Emergency Unit.

Achievements

3. Back from his assignment in Peru, Sergio Vieira de Mello was appointed by the High Commissioner as Head of Career Development and Training Unit in the Personnel Section in January 1980. The challenges Sergio faced in his new job entailed assessing staff training needs through periodic surveys and developing and administering training programmes across the organization. In addition, he developed a career counseling system to identify staff aspirations and skills and determine their needs for training. A special problem he had to deal with was the orientation and training of the new specialized staff to acquire humanitarian experience and knowledge relating to the special situation of refugees. The organization needed to shore up the quality of its staff to shoulder its increasing role in international protection. The specific problems of women refugees became an important agenda in the training programme. Sergio’s preoccupation with dialogue for the peaceful resolution of conflict found ample application in the training programme. UNHCR’s future distinction as an acknowledged centre of knowledge and action on refugees owes much to its early investment in the career development and training of its staff and in creating a versatile rapid field deployment capability.

4. In 1980, the new Emergency Unit under Nicholas Morris began to function. It was the organization’s first effort to establish an organized system of roster, stand-by staff and pre-positioned supply for rapid deployment in the field. This is the machinery that would in latter years serve UNHCR well in its major operations. The Career Development and Training Unit complemented the work of the Emergency Unit especially in the successful development of the well-known, ground-breaking “UNHCR Handbook for Emergencies”.

5. To complement its staff strength, the High Commissioner encouraged the development of collaborative agreements with UNHCR’s traditional NGO partners known as Partners in Action—PARINAC. Sergio played a major role in implementing the tenets of the agreements. These agreements and the joint work with the Emergency Unit, equipped UNHCR with ready rosters for recruitment and rapid deployment of staff in the field earning the organization the reputation of an efficient and reliable agency capable of providing protection and ensuring timely delivery of basic service to refugees. The strategic position of Head of Career Development and Training gave Sergio the unique opportunity to cultivate close relationships with a large number of UNHCR staff who became part of his extended professional and family circle. They have and will continue to miss him dearly.

1981 – 1983

Senior Political Officer, UNIFIL, DPKO, Lebanon 1981-1983

• Brutal Civil war and unabated tension on Lebanese-Israeli border resulting in continuous incursions.

• Occupation by Israel of all Lebanese land south of Litani River and full scale invasion.

• Thousands killed and displaced.

• Security Council Resolutions not respected.

• Worst effects of civil war, Israeli occupation and border tension contained but country left in ruins.

Prevailing Situation in Lebanon in early eighties

1. Beginning of the seventies saw Lebanon engulfed in a ferocious civil war that ended only in 1990. It left the country and its infrastructure in ruins. 20,000 were killed and hundreds of thousands were displaced. Several thousand fled the country and became refugees in neighbouring countries and worldwide. In March 1978, to prevent continuous incursions and rocket attacks by Palestinians into Israel, the latter defying UN objections, invaded Lebanon and occupied all land south of the Litani River. The UN Security Council demanded Israeli withdrawal and decided to deploy a peacekeeping force in the region. Its main task was to ensure the withdrawal of the Israeli troops and re-establish peace and security in the region by helping the Government of Lebanon restore its authority throughout its territory. The United Nations Interim Force in Southern Lebanon (UNIFIL) was deployed on 23rd March 1978 controlling an area of about 650 square km and a population of 4,000. A ceasefire was agreed upon and Israel withdrew from Lebanon but continued to occupy a strip of land along the border.

2. The presence of UNIFIL had little impact on the tension and violence on the ground. Fighting continued between Christian and Syrian forces in Beirut and the situation worsened in the south. A Christian leader, Saad Haddad, supported by Israel, declared independence over a 800 square kilometers stretch of land with 40,000 Christian and Shiite inhabitants. In April 1981, as a reprisal against the Palestinian bombing of the Christian enclaves in the south, Israel bombed Tyre and Sidon. The Palestinians launched rocket attacks on northern Galilea. UNIFIL was powerless and unable to stop the hundreds of deaths resulting from the violence.

Achievements

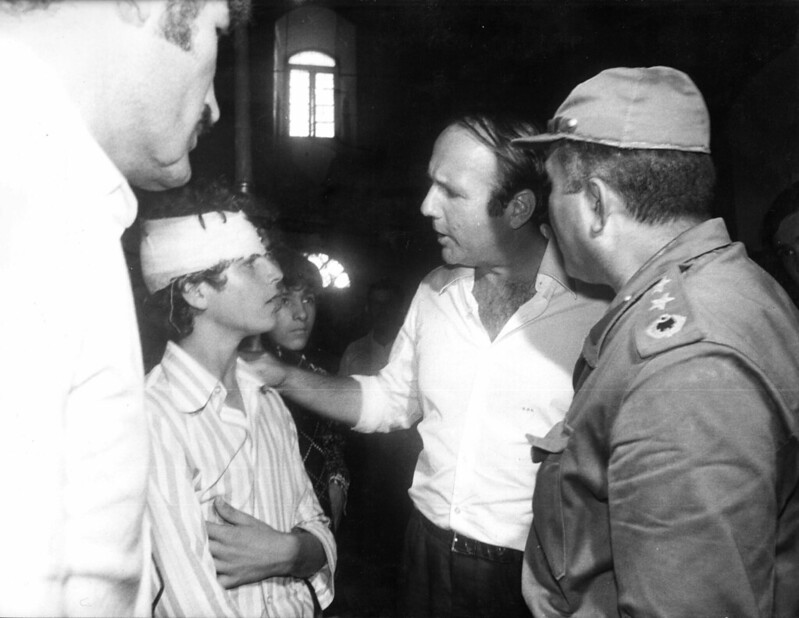

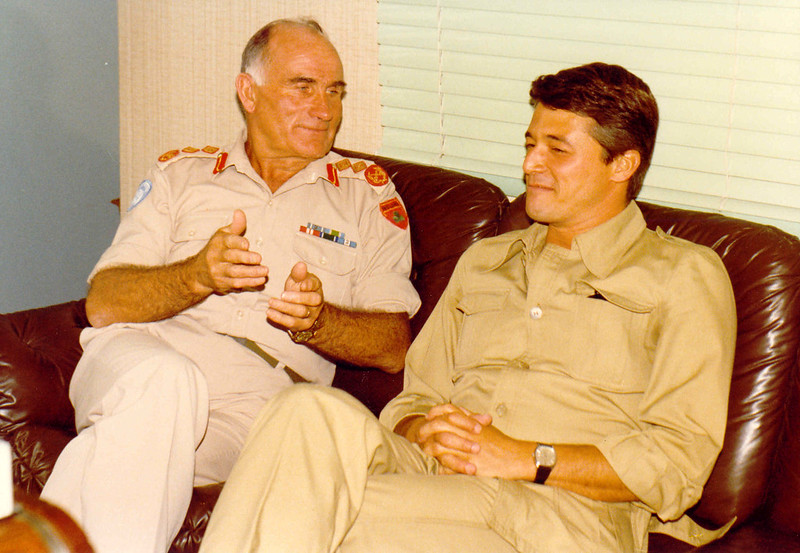

3. In late 1981 at the age of 33, Sergio Vieira de Mello was seconded by UNHCR to work in UNIFIL as Senior Political Officer. With far more experience in humanitarian operations under his belt, the secondment allowed Sergio to shift for the first time to political work in the UN. That part of his career would in the course of time, prepare him to bring into full play, his diplomatic skills and finesse and his talent for dialogue and reconciliation. He served as Special Political Advisor to General Callaghan – in charge at this time of UNIFIL – with whom he built a special rapport and a vibrant team. His responsibilities included liaison between the UN troops and local authorities, assessment and evaluation of the humanitarian needs of the civilian populations and administration of various projects. His easy dealings with the military made his tasks easier . As usual, he performed outstandingly and won the appreciation and admiration of the UN as well as the local authorities and communities he worked so hard to reach and serve. UNIFIL relied on his disarming personality, magnetic charisma and power of persuasion to cultivate dialogue and achieve understanding and cooperation to discharge its delicate mission in the complex and hostile environment of Lebanon.

4. UNIFIL was tasked with the principal mission of maintaining peace and security in the region. However, it had neither the mandate nor the means to impose compliance. Hence the mission that was set up amidst high hopes and expectation ended in failure. This came to a climax in June 1982 when Israel decided to eliminate once and for all the Palestinian military presence in Lebanon by driving out Yasser Arafat and the 15,000 fighters of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). Israel pushed all the way to Beirut and by the end of 1982 its violent attack paradoxically named “Operation Peace in Galilea” had killed thousands, including the massacres of the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. Sergio could not control his indignation and would for years continue to express his anger and outrage over these senseless killings of innocent refugees with impunity. Nevertheless, Sergio and General Callaghan saved no effort in working closely with all the parties in conflict, including PLO and Israel.

5. The Lebanon mission also left Sergio in a dilemma over the role and impact of UN Peacekeeping. On the one hand he believed in and identified with its principles. “Each peacekeeping operation has a specific set of mandated tasks, but all share certain common aims-to alleviate human suffering and to create conditions and build institutions for self-sustaining peace.” On the other, he found himself asking hard questions as to why UNIFIL could not fulfil its mission. He did not spare himself either and wondered whether he could have acted differently. In the end history will be the jury but above all Sergio and UNIFIL did their best under the prevailing situation to save lives and protect innocent civilians caught in conflict.

1983 – 1985

Deputy Head of Personnel, UNHCR, Geneva, 1983-1985

• Refugee problem became one of the major challenges facing the contemporary world

• Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees stuck in camps in situations of legal limbo: “Palestinisation”

• Voluntary repatriation of refugees accepted as the norm for providing durable solutions for refugee.

UNHCR in the mid-Eighties

1. The mandate of the High Commissioner Poul Hartling ended in1985 after having served the organization with distinction for eight years, leading it to win the Nobel Peace Prize for the second time in recognition of its management of the Vietnamese Refugee Crisis and, by extention, for undertaking major operations for the Cambodian and Afghan refugees. His tenure will be best remembered for the recognition and acceptance of the problems of refugees as one of the major challenges facing the contemporary world.

2. In the mid-eighties, UNHCR faced an unenviable dilemma, especially with the countries of asylum. On the one hand, the organization’s mandate empowered it to ensure that refugees were not expelled to countries where they feared for their lives and freedom. On the other hand, the organization was left with millions of refugees in its hands to cater for, often with very high cost for the countries of asylum, precisely because these very governments were unwilling to resettle them on their territories. Several examples of refugees stuck in legal limbo, ironically known as “Palestinisation”, could be cited. Tens of thousands of Cambodian refugees were stuck for years in UN camps on the Thai border. Ten years after the end of the Vietnam War similar situations persisted. In Central America large numbers of Nicaraguans, Salvadorians and Mayas from Guatemala were stuck in neighbouring countries awaiting a political solution allowing them to return home.

3 Accepting the fact that the traditional solutions of local integration or third country resettlement were no longer feasible in situations where the organization had to deal with massive numbers and where the host countries were not inclined to granting resettlement, UNHCR institutionalized voluntary repatriation as the linchpin of its policy of durable solution for refugees. It did so mindful of the budgetary implications but convinced it was the right thing to do in the best interest of the teeming number of suffering refugees worldwide. Consequently, the organization relegated local reintegration and resettlement in third country as remote options. The implications of all this on staff and their morale was enormous. This placed equally heavy pressure on the Personnel Division to meet field demands through rapid deployment of staff and providing them with back-up support. There was also demand on the Division to maintain high staff morale by attending to their concerns.

Achievements

4. After returning from assignment to UNIFIL (Lebanon) where he served as Political Affairs Officer, Sergio Vieira de Mello was appointed by High Commissioner Poul Hartling to the position of Deputy Head of Personnel. He overlapped briefly with the then Chief of Personnel, former Secretary General Kofi Annan. He found the transition from the political work of UNIFIL to the personnel side of UNHCR a bit of an adjustment. Kofi Asomani served as Chief of his old Career Development and Training Unit. He had no choice but to get back into the organization through this route. But being Sergio, he, quickly adjusted and in fact made important contributions, although he was not in his element. The Division of Personnel covered Human Resources Administration, including recruitment, appointments, postings, career development and training. Already familiar with many of the key functions of the Division from his earlier position as Head of Career Development, he focused on the newer challenges of adapting and strengthening the Division as a reliable first port of call for demands from the field for back-up support. An important achievement Sergio and the operational arm of UNHCR, represented by the Emergency Unit, realized was the refinement and strengthening of the effective system of rapid and timely deployment of staff in the field at the height of an emergency. This contributed immensely in winning respect and credibility for the organization, especially amongst donors.

5. The sudden expansion of UNHCR’s operations stretched its capacity to the limit and put immense pressure on the staff, leading often to frustrations and cynicism with the organization. Hence maintaining high staff morale became a major preoccupation of the Division. Sergio led the effort of maintaining close links with the outstreched UNHCR staff in the field as well as those at the Headquarters in Geneva. Because of his out-going open personality, the staff found him easily accessible and ready to listen to them. They trusted him. He devoted much time to dialoguing and counseling staff and attending in a timely manner to their problems, particularly through the Recruitment Officer Jahanshah Assadi whom he depended on to protect him from the overwhelming demands for jobs and favours. It was well known that Sergio had the habit of never leaving office without returning all the telephone calls of the day. Sergio’s conduct of business in this position won him the immense appreciation and gratitude of a large number of UNHCR staff who have and will continue to miss him dearly. Werner Blatter, now a retired senior UNHCR staff who took over the position of Deputy Head of Personnel from Sergio in 1985 and later served as his Deputy when he was Director of External Affairs, was very complimentary of the work Sergio did and the smooth transfer of responsibilities.

1986 – 1988

Chef de Cabinet and Secretary to the Executive Committee, UNHCR, Geneva, 1986-1988

• New High Commissioner at helm of UNHCR

• Aggressive defence of Humanitarian Law.

• Introduction of innovative solutions to refugee problems and encouragement for staff to assume greater responsibilities

• Repatriation promoted including resorting to preventive intervention in countries where a crisis could lead to refugee exodus

• Significant goodwill among countries/governments.

• Conference International sobre Refugiados Centroamericanos (CIREFCA) launched.

UNHCR in mid-late Eighties

1. Jean-Pierre Hocke of Switzerland was elected High Commissioner and took over from Poul Hartling in early 1986.Prior to his appointment, he served as Director of Operations of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). During his tenure, the Indochinese refugee crisis continued. The Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) was launched during Hocke’s time. It enabled the international commmunity to solve the Vietnamese Boat People crisis which began after the end of the war in 1975. Hocke also played a key role in launching the CIREFCA process in Central America, to consolidate peace in the region by extending assistance not only to returnees but also, more broadly, to war-affected populations. During his period in office, UNHCR played an important role in establishing large camps for Ethiopian refugees in the Sudan and for Somali refugees in Ethiopia.

2. Hocke was determined to shake up the UN bureaucracy by introducing new ideas and bringing in young talented people from outside and within the organization. He demanded innovative solutions and put new more horizontal structures in place to stimulate and encourage staff to take responsibilities. He sought to promote repatriation, and even intervene preventively in countries where a crisis could lead to a refugee crisis.

3. Hocke’s solid humanitarian operations credentials and uncompromising defence of the Humanitarian Law, whose corollary is the Refugee Law and his energetic and aggressive style in conducting business, won UNHCR significant goodwill and support, especially amongst the donors. The honeymoon lasted long. The UNHCR Executive Committee received the highest attention of the management, cementing further the excellent relationship with diplomats in Geneva who were instrumental in influencing support for the organization. Kofi Asomani served as Chief of the Secretariat of the EXCOM under Sergio.

4. However, this rosy picture and UNHCR’s extensive successful field operations, which were exalting and appealing to the younger generation (Sergio’s contemporaries in UNHCR), was soon to give way to a deteriorating climate within the organization. Some of the new high Commissioner’s innovative reform started to receive reservations, skepticism and criticisms by governments, inside the UN bureaucracy and in the media. Jean-Pierre Hocke resigned after four years as High Commissioner. His premature departure threw UNHCR into a crisis of confidence among donors and a crisis of identity among staff.

Achievements

5. The new High Commissioner singled out Sergio Vieira de Mello as soon as he came on board and appointed him as his Chef de Cabinet and Secretary to the UNHCR Executive Committee. Sergio, with a select group of other colleagues of his generation, joined the inner circle of Hocke’s top management. The High Commissioner was commended widely for Sergio’s choice as his Chef the Cabinet. Then 38, Sergio used his position as the Secretary to the Executive Committee and turned his full attention to building a strong relationship with Geneva’s humanitarian diplomats. He brought Jahanshah Asadi, who had previously worked with him in the Personnel Division from Bangkok, to asssist him with the Executive Committee function. Here he was on his home ground. His diplomatic skills and flair came into full play. He used it well to establish and maintain one of the healthiest relationships UNHCR had ever enjoyed with its donors and partners. This translated into a healthy funding for the organization.

Asadi recalls a tense situation when Sergio came to him, almost in tears and expressed his indignation at the Chairman of the Executive Committee for wrongly accusing him of taking sides in the negotiations and drafting of the EXCOM resolution/conclusion. True to his character, Sergio could not accept this affront to his integrity and pride. He confronted the Ambassador and the matter was settled amicably.

7. Large refugee camps were established for Ethiopian refugees in the Sudan and Somali refugees in Ethiopia but two major operations dominated UNHCR’s work : Namibia and Central America. True to its new emphasis on durable solutions, UNHCR repatriated tens of thousands of Namibian refugees from Angola back home in time to vote in constituent assembly elections that prepared the way to their country’s independence. This challenging exercise involving a massive airlift was achieved against the background of a very strict deadline imposed by the agreement reached between the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), the Cuban forces backing the Namibian liberation movement and the occupying power, South Africa. Sergio devoted much time to shuttle diplomacy in support of the High Commissioner as they influenced and promoted dialogue between the parties in conflict to benefit the refugees.

8. In May 1989, UNHCR organized a successful International Conference on Refugees in Central America (Conferencia internacional sobre Refugiados Centroamericanos—or CIREFCA) that brought together governments of the region, donors, humanitarian agencies and NGOs. The conference focused on considering a wide choice of programmes directed at creating appropriate conditions for the voluntary repatriation of refugees who had lived for years in countries of asylum. The potential donors received catalogues of emergency and long-term development projects in the countries of origin of the refugees. These projects were conditioned on parallel peace talks between the governments and the rebels under the aegis of the UN and the Organization of American States (OAS). A few years later most of the refugees had returned to their homelands. Sergio gave Leonardo Franco who led the planning and organization of the conference all his guidance and support. The series of dialogues between the concerned governments and rebel groups that led to peace agreements and lasting durable solutions for the refugees in Central America.

1988 – 1990

Director of Asia Bureau, UNHCR, Geneva, 1988-1990

• Intractable refugee situations in South East Asia.

• Geneva International Conference on Indochinese Refugees.

• Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) launched.

UNHCR in late Eighties

1. Thorvald Stoltenberg, then Norway’s Foreign Affairs Minister, was appointed High Commissioner for Refugees in January 1990 to fill the gap left by the sudden departure of Jean-Pierre Hocke. His short term in office marked the beginning of UNHCR’s increased involvement in large-scale UN peacebuilding operations. He oversaw several repatriation operations, especially in Central America. He resigned in November 1990 to return to his previous position as Norwegian Foreign Minister. In May1993, at the height of the Bosnian war, Stoltenberg returned to the United Nations as the Secretary-General’s Special Representative to the Former Yugoslavia.

2. The intractable situation of the Vietnamese refugees (Boat People) stuck for more than ten years in several countries in South East Asia became a major concern for UNHCR. Before leaving office, High Commissioner Hocke and his team led by Sergio Vieira de Mello, then Director of the Asia Bureau, planned an International conference on Indochinese refugees. It was convened by Secretary General Perez de Cuellar in Geneva in June 1989. The conference aimed at reaching agreement on a new comprehensive approach to the Vietnamese Boat People. Refugees and Asylum seekers from Laos were included in the agenda but the conference did not address the question of refugees and displaced persons from Kampuchea, in view of negotiations taking place within a different framework. The conference, attended at high level by major governments and donors, UN agencies and NGOs, was addressed by both the Secretary General and High Commissioner Hocke.

Achievements

3. A major outcome of the June 1989 Geneva Conference was the adoption of a Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA). The CPA was crafted personally by Sergio who had been appointed by High Commissioner Hocke as Director of Asia Bureau in May 1988.The CPA established “new rules of the game” in order to put an end to the “Boat People” exodus which had been going on for more than14 years. A certain “fatigue” had arisen in most of the resettlement countries and consequently the Boat People were stuck, most of the time, in inhuman conditions in various camps in South East Asia. Sergio’s idea was to invite around the same table all the protagonists of the drama: the main resettlement countries (USA, Canada, Australia, the UK and the Nordic countries, among others); the countries of first asylum of South-East Asia ( the Philippines, Thailand, Hong Kong and Malaysia) and the country of origin, Vietnam. In the mid-eighties it was a ground-breaking idea to invite the USA and Vietnam to sit at the same table.

4. By introducing individual status determination and precise guidelines on clandestine departure, the CPA would stop the ongoing exodus. The repatriation option was introduced within the CPA for the Boat People not recognized as refugees (those who failed the individual status determination). This “new” durable solution was accepted by all concerned as the returnees who were in fact economic migrants, received substantial cash grants. A monitoring mechanism was put in place in Vietnam by UNHCR until the end of the CPA. In summary, the CPA presented a challenge to the International Conference to reach a new set of arrangements which safeguarded the fundamental principles of refugee protection while taking into account the concerns of countries of first asylum, of origin and of resettlement. It was adopted unanimously and this strengthened UNHCR’s mandate further. This was the first framework ever developed by UNHCR which combined its protection mandate with material assistance to refugees.

5 While the CPA was a great success as the number of Boat Pepole stuck in camps in South East Asia was dramatically reduced, its implementation started to drift in 1995. Status determination in one of the countries of first asylum was questioned by some of the main resettlement countries. The new High Commissioner, Sadako Ogata, decided that UNHCR had to show leadership again in the CPA and decided to bring it to its logical conclusion. She asked Sergio to resume his responsibility for the CPA which normally would have been handled by the Director of the Asia Bureau. Accordingly, Sergio expeditiously chaired an important internal meeting with the UNHCR Representatives of the CPA countries in Singapore to map UNHCR’s “end game” strategy. This was followed by a meeting with the CPA countries in Bangkok which agreed on how to bring the CPA to an end, including agreeing on a deadline. Consequently, the CPA was officially concluded in February 1996.

1990 – 1991

Director of External Affairs, UNHCR, Geneva 1990-1991

• Changing nature of displacement.

• Concerted efforts to revamp and improve UNHCR’s public relations and image.

• Stronger relationship with UNHCR Executive Committee.

• UNHCR’s Budget and Staff more than double.

• Start of large-scale Emergency Operations.

UNHCR in early Nineties

1. Sadako Ogata, then Dean of the Faculty of Foreign Studies at Sophia University, Tokyo, Japan, was appointed High Commissioner and replaced Thorvald Stoltenberg in December 1990. While in academia, Ogata also held positions in the UN, chairing the UNICEF Executive Board in 1978-79, serving on the UN Commission on Human Rights and as the Commission’s Independent Expert on the human rights situation in Burma (Myanmar). As High Commissioner, she oversaw large scale emergency operations in Iraq, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and the Great Lakes Region. UNHCR’s budget and staff more than doubled during her time in office, and the organization became increasingly involved in assisting internally displaced people and other vulnerable civilians in conflict situations, emphasizing the link between refugees and international security, Ogata strengthened UNHCR’s relations with the UN Security Council.

2. What distinguished the 1990s from earlier decades was the weakening of central governments shored up by super power support and the proliferation of identity-based conflicts, many of which plunged whole societies into violence. The easy availability and growing power of sophisticated light weaponry had increased the destructiveness of even relatively low-intensity conflict. The profits to be derived from war economies often became the main force perpetuating conflict – and an extremely difficult one to reverse. In the post-Cold War period, civil wars and communal conflicts have involved wide-scale, deliberate targeting of civilian populations. That was the stage upon which UNHCR made its entry into the Nineties. The large scale operations that the organization launched to respond to the major humanitarian crises in Northern Iraq, the Balkans, the Great lakes Region and Afghanistan, represented a major shift in the organization’s capacity to engage in several major operation simultaneously. This resulted in a rapid expansion of UNHCR’s functions and operations as the international community looked to it to address some of its most acute dilemmas. The organization became involved in situations of armed conflict and started to work side by side with UN Peacekeepers and other multinational military forces to a greater extent than before.

Achievements

3. Sergio Vieira de Mello was appointed by High Commissioner Thorvald Stoltenberg as Director of External affairs in April 1990. On taking office, Sadako Ogata drew Sergio into her top management team. His first task was to take the lead in rebuilding UNHCR’s public image and restoring trust in the organization. The new High Commissioner relied heavily on Sergio to win this battle. Sergio’s charisma and adept diplomacy were instrumental in enabling the organization to regain the confidence and trust of its hitherto disillusioned supporters, especially the donors. The response in funding was dramatic and soon UNHCR’s budget headed towards a major increase. As then Director of Europe Bureau, John Horekens recalls how Sergio was always a step ahead of the Bureau in the contacts with donors and would then turn to them to follow up these contacts. UNHCR enjoyed an excellent relationship with the donors and the Executive Committee gave the organization its unflinching support.

4. The delicate civil-military relationship that had become the main feature of operations in the major humanitarian crisis countries, especially Northern Iraq and the Balkans, required the High Commissioner and UNHCR to tread carefully. The organization turned to Sergio to craft the right strategies and shape the appropriate diplomatic finesse to steer clear of troubled waters while effectively carrying out its mandate to refugees. He was always in the midst of some of the most challenging dialogues that the organization conducted on behalf of refugees with both State and Non-State Actors as well as the military.

Sergio’s tenure as Director of External Affairs witnessed the start of UNHCR’s era of major operations starting with northern Iraq and the Balkans Sergio played a major role in successfully organizing the High Commissioner’s equally successful high profile visits and missions to the field. His refined diplomacy, power of persuasion and wide network of friends and allies were a real asset for the organization.

1991 – 1993

Director for Repatriation and Resettlement Operations, UNTAC, DPKO, and Special Envoy to High Commissioner Sadako Ogata UNHCR, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 1991-1993

• Devastating Civil War

• More than 1 million killed

• Several hundred thousands fled country

• 200,000 orphans left to care for themselves

• 370,000 refugees repatriated and reintegrated into their places of origin

• Successful negotiations with Khmer Rouge

• Successful breakthrough with Washington for the resettlement of 385 Vietnamese refugees from Cambodia in USA

Prevailing Situation in Cambodia in early Nineties

1. In 1975, the Khmer Rouge seized power in Cambodia and imposed one of the most oppressive rules in the history of mankind. It spread terror in the country, killing over one million and maiming and displacing hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians, most of them as refugees in neighboring countries. Over 200,000 orphans were left abandoned, compelled to look after themselves. This chapter of Cambodia’s history is now viewed as representing one of the worst crimes ever committed against humanity in the Twentieth Century. This reign of terror was only brought to an end when the Vietnamese forces invaded the country in 1978 and routed the regime. It took the UN twelve years for the five permanent members of the Security Council to create a United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) in November 1990. It was the only acceptable formula for compelling foreign forces to withdraw from the country, allow peace to be re-established and give Cambodia and its war-weary people the opportunity to receive massive international assistance leading to recovery, reconstruction and development.

2. On the 23rd of October 1991, following a series of extensive high-level meetings by the five permanent members of the Security Council, the Paris Peace Agreement involving all the parties in the Cambodian conflict was concluded. This was followed shortly afterwards by the appointment of Yasushi Akashi as the UN Secretary-General’s Representative for Cambodia and the launching of UNTAC. UNTAC was structured on seven pillars : military, human rights, elections, civil administration, law and order, rehabilitation and repatriation and resettlement of refugees and IDPs.

Achievements

3. Sergio Vieira de Mello, who was then the Director of External Relations in UHHCR Headquarters in Geneva, was appointed as the Director of UNTAC’s Operations for the Repatriation and Resettlement of Refugees and IDPs and re-assigned to Phnom Penh. He was simultaneously designated by Sadako Ogata, the High Commissioner for Refugees, as her Special Representative in Cambodia. His colleague and friend Anne Willem Bijleveld served as UNHCR’s Country Director.

4. The major challenge that Sergio encountered in assuming his responsibilities in Phnom Penh was in overseeing the repatriation, return and resettlement of hundreds of thousands of refugees, preferably in their homes of origin. He was expected to fulfil this arduous challenge against an array of formidable logistics, security and landmines, not to speak of the skepticism and impatience of the refugees themselves. Every displaced Cambodian wanted and expected to be repatriated in his/her village which was not always easy. Most wanted to be transported together with all their earthly belongings, including domestic animals, which was in most cases difficult to accommodate. In addition, the fragile agreement did not immediately produce tight binding ceasefires, requiring Sergio to constantly negotiate access and concessions with all the different factions. The toughest of his tasks was negotiating with the Khmer Rouge, which was known for its intransigencies.

5. Sergio successfully concluded his mission in Cambodia in June 1993 after repatriating and resettling 370,000 refugees and hundreds of thousands of IDPs. He used his charm and power of persuasion to convince the refugees and his own officials to ensure as much as possible, the returnees and IDPs were reintegrated in their original villages. He also made special efforts to have them carry along as much of their worldly possessions as possible. Against the advice of his colleagues and superiors, he embarked on a lone mission that eventually led to direct negotiations with the Khmer Rouge on their own territory. It led to the Khmer Rouge releasing thousands of refugees to repatriate in their locations of choice in their country. He answered his critics by saying: “I have had to shake hands with many war criminals, because if you want results, you must negotiate with the devil. If you want to see 75,000 Cambodian refugees freely return home, you have to deal with Leng Sary” (the former Chief of Diplomacy and Pol Pot’s brother-in-law).

6. Perhaps the hallmark of Sergio’s admirable negotiating skills and deft diplomacy are best represented by his success in negotiating with a group of lost Vietnamese soldiers (reportedly sponsored earlier by the Americans to fight in Cambodia), and persuading them to surrender their weapons and move to a refugee camp. He later negotiated with the Americans and had the group of 385 combatants and their families resettled in the United States where they reunited with their extended families. The descendants of these fortunate Vietnamese owe much to Sergio for daring to do what he did for their parents and families.

1993 – 1994

Director of Political Affairs, UNPROFOR, DPKO, Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina 1993-1994

• Implosion of Yugoslavia into multi-ethnic conflict resulting in horrific massacres and massive displacements

• 200,000 innocent civilians killed, 286,000 became refugees and several hundreds internally displaced

• Major cities besieged and destroyed.

• Yugoslavia disintegrated into independent states – Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo.

Prevailing Situation in the Balkans in early Nineties

1. Going back to the two World Wars, the Balkans have always been the last straw that triggered the outbreaks of these cataclysmic conflicts. It was therefore a relief to all when in 1945 after the Second World War, late Yugoslav President Josip Bros Tito succeeded in bringing the various independent states under his control and created the Democratic Republic of Yugoslavia. The situation changed drastically after his death on 4th May 1980. Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence on 25th June 1991. In October 1991, the Yugoslav Federal Army made up mostly of Serbs and Montenegrins, besieged and bombed Dubrovnik, in Croatia. Vukovar, a symbol of Croatian resistance fell on 19th November. The atrocities committed by the Federal troops and Serb paramilitary is best remembered by their ruthless massacre of wounded civilians who had been evacuated from hospital. This started a spiraling of senseless bloodshed that would eventually engulf the whole of the Balkans. It extended from Slovenia and Croatia in1991 to Bosnia in 1992 and Kosovo in 1998.

2. In 1992 the UN Security Council established the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in Zagreb, Croatia, with a mandate to initially create a conducive environment of peace and security for negotiating a comprehensive settlement of the Yugoslav conflict. This included demilitarizing the three “United Nations Protected Areas” and ensuring persons residing therein were fully protected from harassment and intimidation by armed elements. In April 1992, when war broke out in Bosnia, UNPROFOR was already on the ground. Its strength was increased to cater for the additional duties of securing Sarajevo airport and ensuring the delivery of humanitarian assistance to the besieged city and surrounding areas. In September 1992, UNPROFOR’s mandate was expanded to support UNHCR to deliver humanitarian assistance through Bosnia-Herzegovina and to protect convoys of released civilian detainees. UNPROFOR was mandated under Chapter VII to only reply to attacks against the UN designated “Security Zones” comprising Sarajevo, Bihac, Tuzla, Zepa, Srebenica and Gorazde in conjunction with NATO.

Achievements

3. As he prepared to leave Cambodia, Sergio Vieira de Mello’s looked forward to his next mission with high hopes. Then UN Secretary General Boutrous Boutrous Ghali had offered him a senior position in the Angola UN mission. He readily agreed to serve in Angola and prepared himself accordingly but this was not to be. Because of his nationality it was not possible for him to serve in the Angola mission. Disappointed but being the soldier he had always been, he welcomed his secondment to UNPROFOR as its Political Director. He arrived in Sarajevo in early October 1993 and started his assignment with some misgivings. However, this soon gave way to enthusiasm propelled by his dynamic sense of engagement with duty and responsibility. He was fully aware of the enormity of his responsibilities. He was expected to give political guidance and support to a UN force of over 45,000 serving in an environment best described as a quagmire.

4. Sarajevo was besieged by Serb artillery. The constant bombardment and the uncontrollable sniping that earned the city the notorious name of a “Sniper’s Paradise” rendered the helpless civilians as easy targets to a formidable force. They had not only to endure the bombardments with rising casualties but forgo food, water, heating and safe passage to hospitals. Sergio was convinced that the only way to break the vicious stalemate was to negotiate directly with the Serbs. The responsibility fell upon his shoulders to lead these negotiations. He relied on his good sense of judgment, flair for diplomacy, courage and daring the impossible to engage the Serbs in a substantive dialogue that made a major difference in the lives of the beleaguered Bosnians.